What is Philosophy? An Historical Introduction

Philosophy 111

Queen’s University

Professor Paul Fairfield

© Paul Fairfield, 2024

Contents

1. Introduction

2. Socrates and Plato

3. Marcus Aurelius

4. Augustine

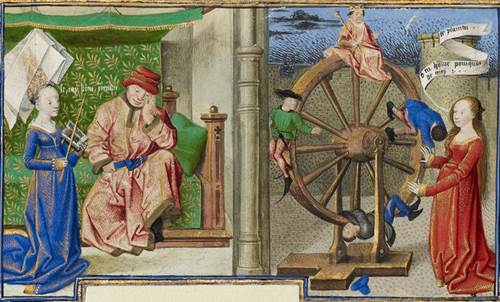

5. Boethius

6. Thomas Aquinas

7. Michel de Montaigne

8. René Descartes

9. Thomas Hobbes

10. Henry David Thoreau

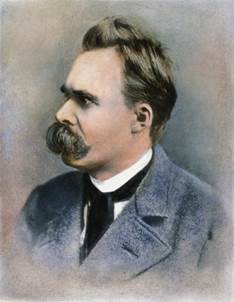

11. Friedrich Nietzsche

Part 1: Introduction

What is philosophy? This question looks straightforward, but when we try to answer it we are confronted with no end of complexity. Let’s begin with the word itself. “Philosophy” is a combination of two ancient Greek words: “philia,” which is one of the Greek words for “love,” and “sophia,” which means “wisdom” or a kind of knowledge that concerns human life and how we are living it. The “philosopher,” then, by its original definition is a lover, in the sense of a pursuer, of knowledge, and where pursuing does not mean possessing. Socrates, the first philosopher we will be looking at, emphasizes that true wisdom is had only by the gods, not by human beings.

This definition will do as a starting point, but philosophy from its beginning in the ancient Greek world quickly broadened out to mean a quest for a rather comprehensive knowledge of human life and of the world in which we find ourselves. Philosophy would soon encompass several subdisciplines, from the study of the ultimate composition and nature of the world (metaphysics) to the nature of knowledge (epistemology), the nature of the good life for human beings (ethics), the nature of a just society (politics), the nature of art (aesthetics), the nature of rational thought (logic and rhetoric), and in time several more specialized subfields, from the philosophy of religion to the philosophy of science, of history, education, mind, language, and some other things. Philosophy has often been said to be the oldest discipline in the West, and it may be the oldest discipline in the Eastern world as well, although our course is an examination of Western philosophy only. Philosophy in the East is a whole other, and equally long, story.

What is the best way to introduce first-year university students (or anyone else for that matter) to philosophy, a field that has about two and a half millennia of history behind it? Different philosophy professors will take different approaches to this. It is not a field like chemistry or biology where we might begin with the present state of knowledge in the discipline, with little or maybe no attention to its history. Philosophy, as many (by no means all) of us see it, resembles art in at least one respect: if we wish to understand the nature of art, I wouldn’t recommend going to an art gallery that exhibits nothing but contemporary artworks. Were this course called “What is Art?” I’d begin with some art history, quite a lot of it actually, before we even get to the modern period. This is because to understand what art is at the present time, you really need to understand what art originally was and how it has developed through the centuries, the various movements, styles, etc. that make up the history of art. Once you know a good deal about art history, you’ll begin to develop a general understanding of art, but it will take time. We might say the same about religion. If this course tried to answer the question “What is religion?” I’d recommend a lengthy tour through the history of at least the major world religions and maybe a few of the smaller ones as well. The same holds for philosophy. Were we to ignore the last twenty-five or so centuries of what the major philosophers in the Western tradition have thought and written and look at the state of philosophy today, we would find it impossible to get our bearings. Realists and anti-realists, idealists and postmodern constructivists, phenomenologists and hermeneuticists, critical theorists and Marxists, pragmatists and positivists, rationalists and empiricists, continental and analytic philosophers—this only partly describes the contemporary philosophical scene, and understanding it will be a lost cause if we don’t first take the time to see what philosophy was in the beginning and some of the many ways it has been passed down to us over the centuries.

The best way, then, to answer the question “What is philosophy?” is historically. My own view is that there’s no other way to go about this, or not well. Were I to break up this class of 150 or so of you into small groups and ask you to reflect upon the nature of consciousness, knowledge, reason, or justice, with zero background knowledge as to what the great thinkers of the past have had to say about these topics, I doubt very much you would come up with anything but for the shallow answers that our culture readily serves up. If we are serious about such questions then we will need to spend a great deal of time listening to what at least some of the more noteworthy philosophers in our tradition have had to say. If this were a course in songwriting, I would sit you down and have you listen for many hours to the great songwriters of the past and present before assigning you the task of composing your own songs, and philosophy is no different in this way. In this course I will be asking you to write two essays and in each of them to formulate an intelligent opinion of your own on a certain philosophical question. Opinions are not formed right out of the gate, or not the kind of opinions that we are seeking in philosophy. Professional philosophers today all have opinions on whatever questions we are writing about, but such opinions are expected to be supported by reasons and are not mere hunches or subjective statements of feeling. Opinions can be and often are mistaken, and everything that philosophers write is subject to rational criticism. It’s best not to think of opinions as something altogether separate from what is called “knowledge.” It is indeed knowledge that philosophers seek, but it’s not the same form of knowledge that a mathematician or a physicist seeks—although this is itself a philosophical question and quite a difficult one: what kind of knowledge are we pursuing in philosophy, and how does it compare to knowledge in other fields? We shall see. Philosophers have convictions about a great many things, but these convictions are always open to question. Nothing is off limits to criticism in this field of study.

There is a certain attitude of mind that we commonly ask the student of philosophy to adopt. One might call it open-mindedness, a questioning attitude, and a rejection of the sort of dogmatism that regards any ideas as off limits to rational debate. It is not that philosophers or students of philosophy lack beliefs. We have plenty of them, but we’re not in a hurry to arrive at any and insist that such beliefs or opinions must be able to withstand rational interrogation. A philosopher is a certain kind of freethinker, not in the sense that what we think or claim to know is idiosyncratic but that we’re not overly beholden to any given worldview at the outset. Ideas and convictions are best regarded as conclusions from arguments, hypotheses which we have found in the course of reasoned inquiry and conversation to be superior to their alternatives, while they typically if not always remain subject to a questioning process which in principle never comes to an end. Philosophy will not end someday, when we discover all the answers to the big questions. In our field, every conclusion becomes a new question or gives rise to new uncertainties which keep us continually moving forward, as in any conversation that is always on the move. Philosophy itself can be thought of as a conversation, one that has been going on for the better part of 3000 years and will likely continue for as long as we’re here.

What we’ll be doing in this course is introduce students to the discipline of philosophy and to the intellectual underpinnings of Western civilization, and the best way to go about this is historically, where this means taking a fairly close look at a number of major thinkers and major philosophical texts that represent several (by no means most) peaks in the vast mountain range that is philosophy. Selecting a reading list is a difficult task in a course like this one, but the texts I have chosen are based on several criteria. First, I have opted for texts that have carried a great deal of influence since the time of their composition. Second, their authors were all making original and profound contributions to philosophy. Third, their relevance to our own time period and to our lives is considerable. Fourth, they are not excessively weighed down with jargon, as much philosophical prose is. Fifth, I am hoping that you will find each of these texts to be relatively engaging and to make for compelling reading. Some historical philosophers are more appealing to first-year students than others, and I have tried to choose authors whom I think you will find relatively lively and interesting. Also, they are not excessive in length; or when a particular text in on the longer side I will not ask you to read it in its entirety but portions only—portions but not snippets. There are innumerable textbooks on the market with titles like Introduction to Philosophy that contain many short snippets of dozens of philosophers and we won’t be using a textbook of this kind but books—proper texts—which contain a beginning, a middle, and an end, in the way that such books are actually written. Asking you to read snippets of a great philosophical text may be compared to asking you to listen to thirty seconds of a five-minute song rather than the song. You neither understand nor appreciate the song after listening to a snippet, and the same is true of philosophical works.

Finally, it’s important to know something about how philosophy has changed through the ages. Since philosophy began and was given its basic trajectory in the ancient world, we will begin there with a few of its major figures, two Greeks (Socrates and Plato) and one Roman (Marcus Aurelius). Philosophy through the very long period of the Middle Ages became more or less wedded to theology, and mostly for this reason courses like this one often skip over this entire era. We will not. Philosophy didn’t disappear for a thousand years, so we will look at a few of this era’s most notable figures (Augustine, Boethius, Thomas Aquinas). In the modern period it changes again, beginning with some transitional figures of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Michel de Montaigne, René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes) and leading into the nineteenth century (Henry David Thoreau, Friedrich Nietzsche). Philosophy doesn’t end in 1900, so why are we not reading anything post-1900, you may ask, and also why are they all men? To the first question the short answer is that philosophy in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries goes in a thousand directions, none of which are understandable at all if you don’t know how such movements and thinkers are responding to a conversation that precedes them. The Department of Philosophy here at Queen’s offers many second, third, and fourth-year courses that deal with philosophy in the contemporary period, but it’s necessary to be grounded in philosophy’s history before trying to make sense of any of this. To the second question, today there are nearly as many women entering the field of philosophy, whether as students or professors, as men, and through the course of the twentieth century philosophy gradually went from being about as male-dominated a field as any to what we now see.

We will be reading several books in this course, and on the subject of books, it does appear that most students who arrive at this or any university today are in the habit of reading books somewhat less than your counterparts of yesteryear. There are likely many reasons for this, but I am afraid there is no getting away from reading books in a course that endeavors to introduce students to philosophy. The best way to learn about philosophy may well be through your own extracurricular reading, following your interests wherever they lead. My first introduction to philosophy happened outside of school, as a high school student reading books independently and for no credit. You don’t need to learn this in an institution, but here we are in an institution, so let’s go about it in a way that makes sense and that I hope you will find interesting. I’ll be asking you to read not more than about 50 pages per week and sometimes less. I’ll be discussing all the readings in the lecture notes that follow and also in class over the next two semesters, but there is absolutely no substitute for sitting down with a good book and reading it for yourself. When you read these books, best to do it in a place that is quiet and where you can focus on what you are reading. Good philosophers choose their words very carefully and their texts are written with great care, and it’s best to read them with equal care and attention. No good work of philosophy can be understood by reading quickly. You must slow down, find a comfortable chair in a quiet place, and read in a completely different way than we typically consume information on the internet, which is usually very fast and with much skimming. If you skim or speed-read your way through these texts, you won’t understand a word. Reading, writing, and thinking are best done slowly. The technology that we all use today has done nothing to slow the mind or to stretch our attention span—quite the contrary—and any proper introduction to philosophy requires that you slow down and stretch your attention span as you would a muscle. The habit of reading books, patiently and thoughtfully, may be the most important mental habit you can form at this stage of your educational career.

Our main aim in this course is to answer the question “What is philosophy?” and in the process introduce you to a field of knowledge that is extremely diverse in terms of the questions philosophers have asked and, still more, the answers they have offered. Our aims do not include attempting to convince you that a given philosopher was correct or incorrect in their views—and this is quite an important point. A university is a place where students may both freely pursue their interests and also believe what they choose to believe freely, without being indoctrinated into what the professor or the institution does. As the professor in this course, I will make no effort to change your beliefs, be they philosophical, political, religious, or what have you. As a rule, when I have an opinion, I write a book or essay that is addressed to other professors in my field and do not take that opinion into a classroom and try to persuade the students, whether overtly or covertly. I do have views, as any philosopher would, on each of the authors we’ll be studying, but don’t concern yourself with what I think about Plato or Aquinas. What matters to you is what you think about Plato or Aquinas—after, that is, you are properly informed about their ideas and have taken time to reflect on them rationally. A university ought to be (and isn’t always) an indoctrination-free zone, and this course very much is. As a student of ideas, you are being asked to think for yourself rather than uncritically parrot the beliefs of your professors or university officials. When professors or university officials express beliefs of this kind, as many will do, be aware that you are under no obligation to make their beliefs your own. As students of philosophy, we always ask for the reasons and the arguments why someone—anyone—holds the views that they do, and we are in no hurry to make their views, or any views, our own. The attitude of a philosopher is that we will believe X once we have sufficiently understood X and have good reasons to accept it, not because an authority figure has told us we must.

A related point I would emphasize is that in this and every course that I teach, all participants—students, teaching assistants, and the professor—have rights of free speech and free inquiry. The writers we will be studying express views that are controversial. Philosophy is controversial by design, and these writers are doing what philosophers are supposed to do. Any students who cannot handle controversial ideas should either broaden their horizons or take a different course—better the former. While I typically refrain from expressing philosophical views of my own in a classroom setting, I also reserve the right to do so. Students also have an absolute right to take any views they like in this course and in your essays, and you are also expected to back them up with an intelligent argument. Philosophers and students of philosophy are freethinkers. Universities are supposed to value disagreement and value it highly. In this course, we do.

Your university career is a time when you are free to explore ideas and fields of knowledge with no pressure to accept definitively any given set of beliefs. The university does not always live up to this promise, but the promise it has long made is to afford all of you the freedom to think, to speculate, and to inquire into different ways of thinking, and without pressure to accept some particular set of convictions. A university is a home to many people with many convictions, and those convictions are conflicting and not always reasonable. The judge of what is reasonable is you—and not you in a vacuum but in conversation with the tradition that is Western civilization. Once you are well grounded in the intellectual underpinnings of your tradition, you are in a position to think critically about it, but not before. We do not criticize what we have not first understood. There are many today—including some professional academics—who will dismiss all of philosophy as nonsense, and not one of them knows what they are talking about. If you hear someone dismiss philosophy with a wave of the hand, ask them how much they actually know about philosophy and which philosophers they have read.

Over the next two semesters we shall be studying a dozen of the most noteworthy figures in the history of Western philosophy prior to the twentieth century. In each case our goals will be essentially two: the first is to get inside the belief system of a given thinker and, to the extent that we are able, try to see the world as they did, and the second is to have something intelligent to say about their ideas. Both aims will be difficult—the first because these thinkers are distant from us in time and place while the second will call upon each one of us to carry out a similar line of reflection to what they themselves carried out. We will not be quick to judge a philosopher’s viewpoint but ensure that we first have an adequate grasp of it and then try to formulate criticisms and supporting arguments and slowly weigh the different arguments before arriving at a conclusion.

What philosophy itself is may be thought of as a conversation that has been going on since ancient times which consists of certain individual thinkers posing difficult but important questions about the human condition in a very broad sense. Each philosopher and text we will be looking at arises from a particular time, place, and culture, and each reflects the conditions in which it arose. Many of the questions they ask are perennial in the sense that they keep arising generation after generation and century after century, and we’ll be focusing mostly on these questions in what follows. To understand any conversation, and to come up with something to say within it, we need to go back and find out how it all started.

Part 2: Socrates and Plato

The story of philosophy in the West actually begins a few centuries before Socrates and Plato, but for our purposes in this course, and simplifying much, our story begins in the fifth century BC. Socrates’ dates are 469-399 BC and Plato’s are about 427-347 BC. A painting of Socrates by the Italian renaissance painter Raphael here depicts him reaching with his right hand for the hemlock that would end his life after his sentence of execution by an Athenian jury. With his left hand he is pointing up, but toward what? The short answer is the Forms, but what does this mean, and why was he sentenced to death?

Before we turn to the theory of the Forms, let’s begin with the story of Socrates himself and the trial that led to his execution. Why would an ancient court sentence a philosopher of all people to death? According to Socrates himself, a philosopher’s vocation is to pursue wisdom, nothing more. How could this be a crime? The answer comes down to us in Plato’s short dialogue “The Apology,” which I have asked you to read and which comes to a little over 20 pages in the Hackett edition (in Plato, The Trial and Death of Socrates, 3rd edition, trans. G. M. A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2000). “The Apology” is Plato’s dramatic depiction of what took place at this trial in Athens in the year 399 BC. Plato was one of Socrates’ young disciples or followers, and he attended this trial. The dialogue he would later compose is an attempt both to describe accurately what took place and who said what, and also to present Socrates as the heroic figure he would come to be viewed as by later generations of philosophers down through the present day. Socrates is still regarded as something of a patron saint of philosophy, somewhat less on account of his ideas than his conduct through life and his rather heroic death.

Let’s begin with the title. The word apology in this context (“apologia” in Greek) doesn’t mean what it usually means for us today but is a formal defence against both the legal charges that have been brought against him and beyond this a defence or justification of his conduct over many years as a pursuer of wisdom in the Athenian marketplace or anywhere else that he found himself. Socrates, aged 70, isn’t sorry, so it isn’t an apology in this sense. On the contrary, he is proud, albeit in a humble way, of how he has conducted himself through his life, in particular in his public life which is the subject of this trial. Athenian courts and trials were not as they are today; the roles of both judge and jury were served by a large jury (501 in this case) of male citizens, and there were also no lawyers. The prosecutor could be any male citizen, and he presented his case to the court while the defendant spoke on his own behalf.

At the outset we find Socrates addressing the jury after his accusers, chiefly a man named Meletus, have made their arguments. He notes how eloquently Meletus has spoken, but the point he urges is that what matters in speech is not eloquence but truth. The truth, as Socrates takes some time to point out, is that his reputation precedes him in this trial. For many years the jurors have heard stories told about this man and how he has repeatedly offended many prominent Athenian citizens by revealing to one and all the limits of their knowledge. A typical Platonic dialogue finds Socrates engaging in intellectual conversation with anyone, whether aristocrat or commoner, who has claimed to be in possession of knowledge. Socrates would begin by asking his interlocutor essentially what it is that they know, how they came by this knowledge, and why the rest of us should accept it. As these dialogues would unfold, Socrates would typically demonstrate that his interlocutor doesn’t know nearly as much as he believes and that he really can’t justify his views at all in the face of rational interrogation. Think of all the things that we all claim to know. We commonly believe, as Socrates’ interlocutors also did, a great deal about morality and politics, science and mathematics, the nature of the world and of the mind, and of a great many things. How much of this actually rises to the level of real knowledge rather than mere opinion? Each of us has a thousand opinions to which we are often emotionally attached, but emotional fervor is no guarantee of truth. Quite the contrary, as Socrates has demonstrated in conversation after conversation, as a consequence of which he acquired a reputation as a nuisance. No one likes to be revealed in public as an ignoramus, and while Plato would always depict Socrates as going about this in a humble and eminently reasonable way, still the reputation of the man went from bad to worse as the years went on.

By the time the trial begins, then, he is already at a major disadvantage as the jury is predisposed against him. Socrates asks the jurors to bracket the matter of his reputation, difficult as that will be, and focus instead on the charges leveled against him and whether there is any truth in them. He distinguishes between his old accusers and his new ones. The new accusations are that, as Socrates puts it, “he busies himself studying things in the sky and below the earth; he makes the worse into the stronger argument, and he teaches these same things to others” (23). His reply to each of these charges is quite straightforward: he hasn’t done these things. He teaches no new doctrines or theories about anything, he deceives no one, and he also does not receive a fee for teaching, although he would have a number of followers, including Plato, who greatly respected him and sought to learn from him. The Greek world at this time had many “sophists,” and Socrates’ accusers were trying to lump him in with this group. The sophists where professional teachers and orators who would travel from city-state to city-state selling whatever knowledge they claimed to possess to whoever would pay their fee—largely young male aristocrats who wished to learn the art of public speaking either in the democratic assembly or in the law courts. This group came to be regarded by both Socrates and Plato essentially as charlatans or intellectual con artists, and we see Socrates here distinguishing himself from them first by pointing out that he has never been paid for practicing philosophy and second by pointing out that he doesn’t claim to possess knowledge. The main doctrine he teaches is the doctrine of ignorance (“docta ignorantia”), and it isn’t exactly a doctrine but a reminder of our intellectual finitude and a plea for humility regarding our knowledge or what passes for it. What I know, in short, is not much of anything—but I know that I am lacking knowledge, and the recognition of ignorance is the first step in the search for wisdom. This first step may be the most difficult, but without it we are (and for Socrates and Plato, most are in fact) doomed to lifelong ignorance.

Socrates then relates a story that concerns the Oracle at Delphi, which was the ancient site of the Temple of Apollo. At this site the high priestess or Pythia would practice the mystical art of divination and answer visitors’ questions most often with a yes or a no. One day, a friend of Socrates by the name of Chaerephon asked the Oracle whether there was anyone wiser than Socrates, and to his surprise the answer came back no. Chaerephon would relate this story to Socrates who was utterly mystified as to what this could mean. How could someone who doesn’t think himself wise be a wise man and indeed second to none in wisdom? This was an extremely serious matter for our philosopher because for centuries the Oracle at Delphi was among the preeminent religious sites in the Greek world, and its pronouncements were taken seriously by everyone in this culture. It became Socrates’ mission, as he tells the jury, to find out whether the Oracle had been right, and his method was to engage in philosophical conversation with anyone with a reputation for real knowledge and find out if they were wiser than he. His recurring experience, as he relates it, was this: “I thought that he [his interlocutor] appeared wise to many people and especially to himself, but he was not. I then tried to show him that he thought himself wise, but that he was not. As a result he came to dislike me, and so did many of the bystanders” (25). Time and time again Socrates would follow this method—what would come to be called “the Socratic method”—of essentially asking questions informally of someone with a reputation for knowledge and demonstrating in the course of reasoned conversation that what they took for knowledge is mere belief, and often enough false belief. What Socrates calls his old accusers, then, are those who took a dislike to him in this way, and they included statesmen, poets and other writers, and especially the sophists. His negative reputation, then, is based not on objectionable conduct but on the empty pride of his former interlocutors.

Socrates then turns to his new accusers or the charges that had been formally brought against him at court. As he says, “It goes something like this: Socrates is guilty of corrupting the young and of not believing in the gods in whom the city believes, but in other new spiritual things” (27). Is any of this true, he asks? The short answer is a simple no. Interestingly, to the charge of atheism or of not believing in the traditional Greek divinities, of which there were many, Socrates does not come straight out and profess his belief in these gods, although he comes close to this in a very short exchange with Meletus: “Is that, by Zeus, what you think of me, Meletus, that I do not believe that there are any gods?” to which Meletus replies, “That is what I say, that you do not believe in the gods at all.” Socrates replies, “You cannot be believed, Meletus, even, I think, by yourself. The man appears to me, men of Athens, highly insolent and uncontrolled” (29-30). We might have preferred that Socrates come right out and state directly that he believes in the gods rather than criticize Meletus. Whether he did actually believe in the gods is open to question, but he does here deny the charge of atheism, however ambiguously. As for professing any “new spiritual things” or doctrines regarding the gods, he denies this directly.

This leaves the charge of corrupting the youth of Athens, which Socrates spends a good deal of time refuting. What might look like an empty charge to us was a very serious matter, and he sets out to ask Meletus a series of questions about what it is to corrupt and also to improve human beings and who it is who does either. Socrates gets Meletus to claim that Socrates alone corrupts people. With what motive, Socrates asks, would anyone do this? If Socrates has been deliberately corrupting his associates, as Meletus claims, wouldn’t he be putting himself in danger, since the corrupted are likely to harm him along with others? Would it not be more prudent to help or improve those with whom we associate, as they are very unlikely to harm us and likely to help us in return? Knowingly corrupting people around us makes no sense. Has Socrates, then, been corrupting the youth unintentionally? If so, this is not a crime and the proper remedy wouldn’t be legal punishment but simple correction, and it is punishment that Socrates’ prosecutors want, and very serious punishment at that. A bit later in the dialogue Socrates adds: “If I corrupt some young men and have corrupted others, then surely some of them who have grown older and realized that I gave them bad advice when they were young should now themselves come up here to accuse me and avenge themselves” (36). None of these men do so; on the contrary, Socrates was commonly regarded by such men as a wise man whom they sought to emulate.

Who are the true corruptors of human beings, who are their improvers, and which group is more numerous? Socrates suggests an analogy between those who benefit human beings and horse trainers. Anyone can corrupt or harm horses, while the skilled horse trainer is more rare. In a similar way, and for the same reason, the true benefactors of humanity are few (because only a few have the knowledge), their corrupters many—although the latter are likely to corrupt others through ignorance rather than malice. Socrates gets Meletus to claim that everyone in Athens improves the young with the sole exception of Socrates, and the claim is implausible on its face.

Another important theme that emerges in “The Apology” is death, a theme to which Socrates would return in “Crito” and “Phaedo,” which are included in our volume and are also fascinating reading. Socrates states that he doesn’t fear death, and that fearing death is irrational. His prosecutors want him executed, so it behooves the philosopher to say something on the subject of mortality. We don’t know what happens to us after death, he says, and it is irrational to fear the unknown. All that matters to one who is rational is that one do what is good and pay no mind to the fear of death that so many have. He will later state that if the traditional stories of the afterlife are true then the soul is immortal and after death Socrates can look forward to meeting the great heroes and thinkers of the past and to engaging them in philosophical conversation. Maybe they have real wisdom to impart. This is hardly something to fear. Socrates is at once advancing a philosophical point about immortality and likely engaging in some provocation of his prosecutors and perhaps the jury as well. The jury is likely to have expected Socrates to cower in the face of these charges and to plead for his life. He instead does the opposite and demonstrates even here the philosophical way of life he had been practicing throughout his life, presumably with full knowledge of the probable consequence of the sentence he would soon receive. He goes further and tells the jury that if they acquit him on the condition that he cease to practice philosophy as he has been doing, he will refuse: “Men of Athens, I am grateful and I am your friend, but I will obey the god rather than you, and as long as I draw breath and am able, I shall not cease to practice philosophy, to exhort you and in my usual way to point out to any one of you whom I happen to meet: ‘Good Sir, you are an Athenian, a citizen of the greatest city with the greatest reputation for both wisdom and power; are you not ashamed of your eagerness to possess as much wealth, reputation, and honors as possible, while you do not care for nor give thought to wisdom or truth, or the best possible state of your soul?’” (32). Socrates’ mission has been given to him by the gods, and it is to serve the people of Athens in a way that they are unlikely to appreciate: “I was attached to this city by the god—though it seems a ridiculous thing to say—as upon a great and noble horse which was somewhat sluggish because of its size and needed to be stirred up by a kind of gadfly” (33). A gadly is a nuisance, like a mosquito that won’t go away. The people of Athens, or any other place, are intellectually sluggish and most live unexamined lives. What they need is an intellectual awakening, and this is exactly what they don’t want. They don’t want it, but they do need it, for “the unexamined life is not worth living” (39).

The jury disagrees and finds him guilty. The trial now moves into the sentencing phase, which is also determined by a majority vote by the jury of 501. After Meletus requests a sentence of execution it is Socrates’ turn to request an alternative sentence. This is the point at which the prudent course for Socrates, or the usual one anyway, would be to plead for a relatively light sentence such as a fine and beyond this to show some remorse for the crimes of which he has now been convicted. He does the opposite and alienates the jury even further, and no doubt on purpose. The question he must now speak to, as he points out to the jury, is what just consequence is owing to him given everything that has been said in the trial to this point. The prosecutors have convinced a majority of the jury, but it does not follow that what the prosecutors have alleged is true. It is not true, therefore Socrates does not deserve punishment but reward, as he now tells the jury. What reward is fitting, he asks, for a public benefactor who has neither money nor reputation nor power? Athletes who have won victories at the Olympic games are rewarded in the form of free meals in the town hall, as are some other public benefactors. Socrates suggests this as his reward, and the jury is not amused. Given the choice between execution and free meals, the jury opts for execution and by a wider margin than had found him guilty in the first place. Banishment will not do, Socrates points out, since if he is driven out to another city he will go about the same activities there as in his native Athens.

Execution it is, then, but Socrates warns the jurors that he is not the only one of his kind and that after his death there will be other philosophers, including his followers, who will be younger than him and more energetic. The people of Athens can put an end to Socrates’ life, but what they cannot stop is the larger attitude of mind and way of life that he represents. He ends on the note that “there is good hope that death is a blessing, for it is one of two things: either the dead are nothing and have no perception of anything, or it is, as we are told, a change and a relocating for the soul from here to another place. If it is complete lack of perception, like a dreamless sleep, then death would be a great advantage” (41). If the soul is immortal, life in Hades will be very pleasant as “I could spend my time testing and examining people there, as I do here, as to who among them is wise, and who thinks he is, but is not” (42). “The Apology” ends on this note.

Here we see a statue of Socrates on the left and Raphael’s painting of Plato on the right, gesturing upward toward the Forms or the ideas which in Plato’s metaphysics constitute a transcendent order of being. More on that later.

The second and somewhat longer dialogue of Plato’s that we will look at is the Symposium (trans. Christopher John Gill, New York: Penguin, 1999) which was written by Plato some years after “The Apology” but that recounts an event that occurred some years earlier. It again depicts Socrates engaging in philosophical dialogue with a number of aristocratic men, this time at a “symposium” or drinking party which, according to Greek custom, would take place in the evening after dinner at the home of one of the participants who would act as host of the banquet. A symposium today is a panel of speakers and alcohol isn’t usually involved, but a Greek symposium was a semi-formal occasion in which food and wine were served, flute girls would provide the entertainment before the speeches began, and a good time was had by all. The symposium was also an “agon” or friendly contest; the invited guests would be given a question, and they would take turns giving speeches that tried to answer the question. The question on this occasion is, what is love?

The Greek word is “eros,” so we’re speaking of erotic love. There are several ancient Greek words for the different forms of love: “philia” (friendship), “agape” (charity), “xenia” (hospitality), “storge” (familial love), “philautia” (self-love), and eros. Eros was the god of sexual love, and the speeches were to praise the god while also defining what this form of love actually is. The seven speeches are delivered by Phaedrus, Pausanias, Eryximachus, Aristophanes, Agathon, Socrates, and Alcibiades, and as in so many of Plato’s dialogues Socrates’ speech expresses a viewpoint that is more or less indistinguishable from Plato’s own. Plato himself did not attend this event but recounts the story some years later in dramatic literary form. The result is one of Plato’s more artful dialogues on a theme of perennial interest.

The dialogue opens with Apollodorus agreeing to relate to an unnamed companion the content of the speeches while they walk along a road to Athens. The banquet took place at the house of Agathon, a tragic poet. As the guests prepare to dine, Socrates doesn’t immediately join them but is standing on a neighbor’s porch lost in thought, as was his habit. Socrates arrives midway through dinner and remarks to Agathon that he looks forward to hearing the latter’s wisdom for Socrates himself has none. Eryximachus proposes the topic of eros and the guests readily agree. Socrates also agrees and adds somewhat uncharacteristically that “the subject of love is the only one I claim to understand” (9). We will see what he means by this when we get to his speech.

The first speaker is Phaedrus. Eros, he says, has long been honored as among the most ancient of gods and is without parents: “Because of his antiquity, he is the source of our greatest benefits. I would claim that there is no greater benefit for a young man than a good lover and none greater for a lover than a good boyfriend” (10). One will immediately note the accent on erotic love between men, which will remain a recurrent theme in this dialogue. This wouldn’t have surprised Plato’s readers, as such relations were commonly regarded in ancient Greece somewhat differently than in modern times. As our translator notes in the Introduction to this volume, “A familiar pattern in Greek culture in the Archaic (seventh-sixth century BC) and Classical (fifth-fourth century BC) periods is that in which an adult male is attracted to a boy or young man, especially when the latter is between puberty and growing a beard (which marked the entry into full manhood). Scholars usually see this relationship as an asymmetrical one: the older partner (the lover) takes the initiative and gains greater sexual pleasure; the younger (the boyfriend or loved one) gains the friendship and help of the older man” (xiii-xiv). The relationship would typically be short-lived and the older man would often be married. In any event, love in this sense is to be understood variously as between men, between women, or between a man and a woman. Eros remains one, regardless of these considerations. This point does not come into question in the Symposium.

Phaedrus continues: no good—not family, reputation, money, status, or anything else—is more vital than love in imparting a “sense of shame at acting disgracefully and pride in acting well” (10). Without this sense of shame at vice and pride in virtue, no one will live a good life, and the great teacher of this sense is Eros. None of us would wish to be seen by our beloved in a shameful light, and by the same token the wish to impress our beloved inspires many a noble action. “Besides, it’s only lovers who are willing to die for someone else; and this is true of women as well as men” (11). This kind of love underlies countless acts of courage and nobility while discouraging more effectively than any other factor in human life their opposites, Phaedrus says. The lover is more inspired and god-like than the beloved, and is more commonly praised. Love, he concludes, “is the most ancient of the gods, the most honoured, and the most effective in enabling human beings to acquire courage and happiness, both in life and death” (12).

Pausanias is next, and his opening move is to draw a distinction between two kinds of love. Eros is inseparable from Aphrodite, and “since there are two kinds of Aphrodite, there must also be two Loves” (12). These two divinities are Aphrodite Urania, daughter of Uranus, and Aphrodite of all the people, daughter of Zeus and Dione. The second kind of love is common to all, aristocrat and commoner alike, and it is a love more of the body than the mind. Here one wants only to obtain the object of one’s desire, whether by means moral or immoral. The beloved may be male or female, in contrast to the first kind of love which is directed at young males. This heavenly or transcendent Aphrodite is uncommon and is an affair more of the mind than the body. It has an intellectual quality and forswears all violence. If lover and beloved are both of good character, there is nothing disgraceful in this type of relationship, Pausanias says, although moral norms regarding this will vary from one place to another. His own view, as he states, is that a relationship of this kind is neither morally good nor bad in itself but depends on how it is conducted. “It is wrong to gratify a bad man in a bad way, and right to gratify a good man in the right way” (16). Anyone, good or bad, can love in the common way where it’s the body that is desired rather than the mind and character of the beloved. There is nothing especially noble in this, and it is inconstant because the thing that it loves—the body—is inconstant or changes over time. In contrast, transcendent love is constant because its object is the character of the beloved, and good character is constant. It is preferable for the beloved to resist the lover’s advances for some period of time while the latter persists without coercion. The passage of time acts as a kind of test of the character of both, so falling in love quickly is not advisable. The lover being older and ideally wiser than the beloved, it falls to the former to benefit the latter by means of favors and education while the beloved confers benefits of a more immediate kind. The beloved, then, aims “to gratify a lover in the hope of gaining virtue” (17). This kind of relationship with a younger boy is rightly forbidden since the boy doesn’t yet possess the requisite qualities of mind and character.

The next speaker is Eryximachus, who takes Pausanias’ distinction between the two loves as his starting point. Drawing upon his experience as a doctor, Eryximachus suggests that love is found not only among human beings but in all forms of animal and vegetative life: “It’s inherent in the nature of bodies that they manifest these two kinds of love,” he states (18). Love may be thought of as a certain kind of order or a correct relation between opposites. A healthy organism desires different things than the diseased, and love in one is different from the other. It’s medically good to gratify the healthy parts of the body and bad to gratify the diseased parts. The physician tries to bring into right order such opposite elements as hot and cold, dry and wet, and so on, and something similar can be said of agriculture, music, and athletics. In each case we are trying to bring opposing elements into a condition of harmony or order, and this order we call love. In agriculture a proper harmony of hot and cold, dry and wet, produces a good harvest while a disorder of these elements produces the opposite. The same principle governs human relationships which may be harmonious or disharmonious, properly or disordered.

Next up is the famous comic playwright Aristophanes, who changes the subject somewhat from the previous speeches to the topic of the sexes. Our common belief is that there are two sexes, male and female. In the mythical story that he now relates there are three: male, female, and a third androgynous state which was the original condition of human nature. The word androgynous, he points out, is commonly spoken of as an insult, but in the beginning of our species it was the natural state of all humans, and it combined equal elements of male and female. The division between male and female came later. In its original state, as he puts it, “the shape of each human being was a rounded whole, with back and sides forming a circle. Each one had four hands and the same number of legs, and two identical faces on a circular neck. They had one head for both the faces, which were turned in opposite directions, four ears, two sets of genitals, and everything else was as you would imagine from what I’ve said so far” (22). Round in form and remarkable in strength, human beings became full of hubris (a vice dreaded by the Greeks) and mounted an assault on the gods which was ultimately unsuccessful. To punish mortal humanity, Zeus devised a plan to permanently weaken human beings, declaring: “I shall now cut each of them into two; they will be weaker and also more useful to us because there will be more of them. They will walk around upright on two legs. If we think they’re still acting outrageously, and they won’t settle down, I’ll cut them in half again so that they move around hopping on one leg” (23). It was Zeus, then, who put an end to our androgynous nature and made us all male or female. Each of us, having been cut in two, longs passionately to this day for a reunion with our other half, and this is the origin and the nature of erotic love. The beloved for whom each of us searches is not ultimately an other but part of one’s own being, and each one of us has one. This is why lovers often speak of the beloved as completing us or making us whole. The act of love “tries to make one out of two and to heal the wound in human nature” (24). The real nature of love, then, is to return to our original nature or to come as close to this state as possible, “to find a loved one who naturally fits your own character” (27). This is why like seeks like, a phenomenon well known to the ancient Greeks.

The last speech before Socrates is by Agathon, a poet at whose home this symposium is taking place. His aim, he states at the outset, is to praise the god by describing its nature rather than concentrating on the benefits it provides to human beings. While all gods are happy, Eros is happiest as it is the best among them and the most beautiful. It is not the oldest of the gods, as has often been said, but is the youngest and the most beautiful. Eros “always associates with the young and is one of them; the ancient saying is right, that like always stays close to like” (29). Love is forever young and is essentially an affair of youth. It is at once beautiful and virtuous and causes no harm to the beloved. It doesn’t use force but requires consent in all matters, and it is just and moderate. Love masters the other pleasures and avoids access. It is courageous, wise, and poetic. “Everyone turns into a poet, ‘even though a stranger to the Muses before,’ when he is touched by Love” (31). Love is full of good will and generosity, inspiring virtuous acts of many kinds.

It is now Socrates’ turn to speak, and he begins as he often would by acknowledging both the difficulty of the task and his own inadequacy in competing with the speeches that have been given. There is more than a hint of irony in this, as Socrates now tells us that if it is truth we seek rather than beautiful words, he may be able to help us with this. He begins by asking a series of questions to Agathon, demonstrating his usual philosophical practice which is to formulate ideas along with others in a dialogue and by asking questions with an attitude of intellectual humility. He does not play the expert but does nearly the opposite of this. In the resulting dialogue his and Plato’s views, which are now impossible to distinguish, will come to the fore. His opening move is to ask about the object of love: does the lover possess what they love or not? Agathon replies that we usually do not possess the thing or the person we love. Socrates replies that it is more than merely usual or likely that we lack the object of our love but it is necessary. To love is to pursue something or someone we desire. We desire not what we have in the sense of securely possess but what we lack. In the case of something like health, the healthy commonly say that they desire good health, but this isn’t exactly true. We desire health if we are unhealthy, that is, when we lack the object of desire. Although the healthy will say they desire good health, what they really mean is that they desire that in future they will remain healthy. Our future good health is not something we currently possess. What the healthy want is not to be healthy but to remain healthy, and the difference is important for Socrates. We love only what we lack and need. This doesn’t mean that the married person doesn’t love their spouse but that one doesn’t possess the beloved any more than the philosopher possesses wisdom. To love is to pursue, not to own, and to desire the future or continued presence of the one we love. Agathon has said that Eros is a good and a beautiful divinity, but is this true? We don’t love what is bad or ugly but what is good and beautiful, and love is itself good and beautiful, or so Agathon has asserted. Socrates has just shown that love is of what we lack, so if love is of or for the good and beautiful then love itself is neither beautiful nor good.

Socrates then proposes to relate what had been taught to him in his youth about love by a somewhat mysterious woman named Diotima. This wise woman, Socrates tells us, formulated for him the same argument he had just put to Agathon, that if we love only what we lack then love itself is neither good nor beautiful. Rather, the beloved is these things, and to love someone or something is not to have it but to desire and to pursue it. Eros, accordingly, is at once a matter of passion and action, or it is simultaneously something that we feel and something that we do. It doesn’t follow that because love is not good, it is bad, or because it is not beautiful, it is ugly. Love is none of these things, and it is also blasphemous to say of the god that it is bad or ugly. Love is “something in between” the good and the bad, the beautiful and the ugly, just as a person can be intermediate between wise and ignorant (38). Diotima then asserts to Socrates that love itself cannot be a god, much to his surprise. Everyone, he says, believes Eros a divinity, and not just any divinity but one of the greatest and most beautiful among the many Greek gods. Diotima replies that not only she but Socrates himself denies the divinity of love. How so, he asks? The gods, she explains, are happy and have what is good and beautiful; the lover does not but desires these things. If the lover lacks these things then the lover is not a god. Is Eros a mortal, then? Her answer is again that love is neither divine nor mortal but intermediate between them. Love “is a great spirit, Socrates. Everything classed as a spirit falls between god and human” (38). The function of spirits, she says, is to “interpret and carry messages from humans to gods and from gods to humans. They convey prayers and sacrifices from humans, and commands and gifts in return for sacrifices from gods” (39). Gods, Diotima tells Socrates, communicate with human beings not directly but through the intermediary of spirits, and Eros is among these spirits.

The Greek gods had parents and a lineage, and Socrates now asks her about the identity of Eros’ mother and father. In the story she tells, Eros’ father is the god Resource and his mother is the god Poverty. Taking after his mother, love is always in need, yet since Resource is his father he desires and works hard to attain good things. Eros is neither rich nor poor, neither mortal nor immortal, neither wise nor ignorant but in between each of these opposite pairings and now one, now the other. He is a lover of wisdom, and where again the lover does not finally attain what he loves but is oriented toward it.

Are all people lovers or only some? Everyone desires what is good and beautiful, and everyone desires happiness, but would we call all people lovers? Also, what is it that we most ultimately want, among the many things that we desire and pursue? We pursue many values, from education and knowledge to material goods and money, status and reputation, family, freedom, security, health, and some other things. We also tend to pursue the same things, so why do we call some lovers and not others? Ultimately, Diotima proposes, we are all lovers and “the only object of people’s love is the good” (42) in the sense that everything we desire, we desire because it is good or because we think it so. We’re all directed toward the good, but we approach it in different ways, while love itself Diotima sums up as “the desire to have the good forever” (43).

If we desire the good and pursue it in many ways, which way is best? She answers, “Love’s function is giving birth in beauty both in body and in mind” (43). What does this mean, Socrates asks? Diotima answers that “All beings are pregnant in body and in mind, and when we reach a degree of adulthood we naturally desire to give birth” (43) to what is good and beautiful. Literal pregnancy and the act that precedes it are acts of creation, and the same can be said of philosophical conversation that leads to knowledge, and a great many other things in human experience. We’re always giving birth in one way or another, creating what is beautiful or good, and “reproduction is the closest mortals can come to being permanently alive and immortal” (44). A writer writes a book, a builder builds a house, a parent brings a child into the world, a teacher shapes a student’s mind, and so on, where in each case our hope is that the created thing will outlive us. The created thing is not identical with its creator, but it is “of the same type” (45). “So you shouldn’t be surprised,” Diotima adds, “if everything naturally values its own offspring. It’s to achieve immortality that everything shows this enthusiasm, which is what love is” (45). Everyone wants to be remembered after they die, and not merely remembered but remembered for their virtues and good deeds. This is why eulogies speak of the virtues of the dead and not of their vices. It is our way of honoring the dead. We admire dead philosophers like Socrates or Plato on account of their ideas or their texts which remain with us and constitute a form of human immortality.

Diotima continues, when we’re young we’re naturally drawn toward a beautiful body, but in time this passion should be tempered by realizing that the beauty of one body is much like the beauty of another. We should then see the good of beautiful bodies in general and not just one; our passion for a single beautiful body ought to be moderated and regarded as a minor matter. Next, the beauty of minds ought to be seen as having more value than bodily beauty. We gradually ascend from the bodily to the mental, from the material to the immaterial, and from the world that the senses put us in contact with to a transcendent order with which our reason alone brings us into contact. Better than beautiful things is “beauty itself, absolute, pure, unmixed, not cluttered up with human flesh and colours and a great mass of mortal rubbish” (49). Plato will say the same of the good: higher than good things is the Good itself (what he will call the Form of the Good), which is the proper object of philosophical inquiry. More on that below.

Such is the account of love, Socrates tells his audience, that Diotima imparted to him and his speech ends here, although the dialogue continues a while longer. Alcibiades now shows up drunk and unruly, asking to be admitted to the banquet. Alcibiades is a military general a good deal younger than Socrates and also enamored of his former teacher. Agathon allows him in and Socrates mentions to his host the relationship that he and Alcibiades once had. Alcibiades wishes to give the final speech which turns into a eulogy more for Socrates himself than for Eros. He begins by mentioning that Socrates never seems to get drunk but always remains in possession of himself no matter how much he drinks and regardless of what is going on around him. Alcibiades, by contrast, is not known for self-control and proceeds to offer a drunken speech about his unsuccessful attempts to seduce Socrates, whom he describes as a master of restraint and moderation. Toward the end of his speech he relates a story about when he and Socrates were on military campaign together and one morning the philosopher stood alone outside on a cold morning to think about some problem and remained silently there throughout the day, to the amazement of all who saw him. “In the end, when it was evening, some of the Ionians, after they’d had dinner, brought their bedding outside (it was summer then), partly to sleep in the cool, and partly to keep an eye on Socrates to see if he would go on standing there through the night too. He stood there till it was dawn and the sun came up; then he greeted the sun with a prayer and went away” (60).

The speeches are now at an end, but the drinking party is not. More people arrive and all are drinking through the night. Socrates again doesn’t sleep but remains up all night drinking and conversing, now on the subject of literature. In the morning he takes his leave and begins a normal day.

We have been focusing on Socrates, but to repeat, scholars find it difficult and often impossible to distinguish the philosophical viewpoint of Socrates from that of his student Plato. The philosophy of love that Socrates relates in his speech he attributes to the wise woman Diotima, but we can presume that it represents Socrates’ own view as well and also Plato’s. Plato’s early dialogues are generally thought to present a more or less accurate characterization of the historical Socrates while in his later writings Socrates continues to appear as the main figure but becomes something of a literary mouthpiece for Plato himself. I’ve alluded above to the concept of the Forms, and before concluding this section of the course it’s important to discuss this doctrine of Plato’s some more.

In a couple of the paintings above we see both Socrates and Plato pointing upward. What this signifies is that they are urging us to look up to a higher realm of ideas or what Plato would call Forms (usually in the upper case). These Forms, Plato believes, comprise a transcendent and knowable realm that is above and in some sense more real than the world of ordinary experience or the world of material nature. Philosophers, Socrates and Plato are urging us, must look up, as a ship’s navigator looks up at the stars rather than focusing always on what lies ahead. This, in a sense, is what Socrates is urging his fellow Athenians to do: to look up or to reflect in a serious way on what passes for knowledge in our culture, to think in a more rational and critical way about the many ordinary opinions that we all hold. How many of those opinions amount to real knowledge? For Socrates and Plato, the answer is not many. Knowledge and opinion are not the same.

In the theory of Forms that Plato would develop, the various objects that we find in our world—from trees and animals and stars to shadows, works of art, numbers, and so on—are all properly regarded as copies or imitations of these Forms. Take a painting of a person, for example. A painting of Socrates isn’t Socrates himself but a copy or an imitation of the man, and as a copy it is in a sense less ultimately real. The painting has less being than Socrates himself, or it possesses a lesser type of reality. Another example is this symbol: 3. This symbol of the number three is not identical with the number itself but it’s a copy of it. As a copy, it again has a lesser kind of reality than three itself or what we might call three-ness. Another example: you and I are both humans, but we are not humanity. We are examples of humanity, not humanity itself. All the symbols in the world of the number three do not amount to three or three-ness itself. The latter is better understood as a definition or something closely resembling a definition. Similarly, humanity is a definition, not a sum of actual flesh and blood human beings. Individual humans change—we grow, our characteristics change, our behavior changes—but humanity remains what it is. Some things change and others do not, and for Plato and many other Greek thinkers, things that change are in a sense lesser or inferior to things that don’t, such as the gods.

Forms (or what are sometimes called Ideas, the ancient Greek word is “idea” and also “eidos”) don’t change. Change and contingency are marks of imperfection, and it is generally characteristic of the world that we perceive with our senses, the world of nature, that it changes continually. The triangle that I draw on a blackboard also changes and can be erased or modified. It is neither a perfect triangle nor what we can call “triangle itself.” It is a copy of triangle, or it is “a” triangle, not triangle. A straight line, to take another example, can’t be drawn on the blackboard but belongs to a different order of being than the physical. It is a properly mathematical object, and these can be copied or represented in the form of physical objects, but imperfectly.

Socrates spends some time in another dialogue, the Republic, discussing the Forms, but he doesn’t spend a lot of time actually demonstrating their existence. Plato does have a few closely related arguments as follows. First, a science such as medicine deals not with my health or yours but with health itself. Health must therefore exist as a unified object of knowledge; this object is a Form. Second, my cat Fluff is one particular cat, not cat itself or cat-ness. Cat is a general concept of which Fluff is only one example. Cat must exist (not just cats), and this is a Form. Third, even if every particular cat in the world were to disappear, cat-ness would not, and nor would it change. Again, cat or cat-ness itself is a Form. When you think about it, we actually spend a fair amount of time talking and reasoning about objects that the senses never make contact with, such as justice or the number three. We can point to just laws or just actions, or to three objects or a mark on a blackboard, but the senses don’t make contact with three itself or justice or beauty or the good itself. The fact that we reason about and know the truth about them suggests that they exist in a reality to which the senses don’t have access. Plato scholars have spent a great deal of time trying to analyze Plato’s theory of the Forms, but Plato’s dialogues themselves spend curiously little time discussing it. He’s clear that there is a Form of the Good, justice, beauty, and the kind of concepts that philosophers are generally interested in, but it’s not entirely clear whether there’s a Form for every object in the world. Is there a form of computer or of toilet? It’s uncertain, although in Book 10 of the Republic Socrates does allude to a Form of couch or bed.

The foremost or highest Form is the Form of the Good (upper case), which Socrates illustrates, again in the Republic, by means of the metaphor of the sun. As the sun illuminates or renders intelligible everything in the world of nature, so the Form of the Good illuminates or renders intelligible all the other Forms which comprise the intelligible realm. Socrates throughout this dialogue wants to know what is the Good, where this means not what things are good but what is goodness itself. Once the philosopher has beheld the Form of the Good, he or she can then understand all the other Forms and also gain a deeper understanding of mathematical objects, physical objects, and images and shadows.

For more on Plato’s theory of the Forms and his larger metaphysical, political, and educational philosophy, see my lecture notes for “Ancient Greek Philosophy” (Philosophy 233) on the same website, although I am not holding you responsible for that material in this course. Socrates, Plato, and his student Aristotle are the three foremost philosophers of ancient Greece and we don’t have time to do more than introduce the first two in this course, but Plato and Aristotle both made major contributions to metaphysics and the theory of knowledge, moral and political philosophy, and the entire field of philosophy in the ancient period. My lecture notes for 233 cover Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’s main book on ethics, the Nicomachean Ethics, but there is so much more to their thought than I can cover in these courses and there is also far more to ancient Greek philosophy than these three thinkers.

We have arrived at the conclusion of the Symposium. It is a fairly short text, so make sure you read it from beginning to end.

Part 3: Marcus Aurelius

We now jump ahead several centuries to the second century AD and to the Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius, whose dates are 121-180 AD. He served as Roman emperor for the last nineteen years of his life, which was a long time to serve in that position. Many emperors lasted less than a year in that role, and Marcus to this day has a reputation as one of the greatest of the Roman emperors as well as one of the primary representatives of the Stoic school of philosophy. The Meditations (trans. Martin Hammond, New York: Penguin, 2006) is a concise book of reflections on life that he wrote in Greek (long regarded as the language of higher culture while Latin was the everyday language) during the last decade of his life while on campaign along the northern border of the empire. It is essentially a book of private reflections which was likely not intended for publication but for personal edification alone. The above photo is of a bronze statue of the emperor which is in Rome. This being a short text of twelve chapters or “books,” I’ll ask you to read all twelve; if you have a different edition of the book, that is fine.

Let’s start with some basics: what is Stoicism? It can be described as a movement in ancient Greek philosophy which continued throughout the several centuries of the Roman era and went into eclipse around the fourth century AD when Christianity became the official religion of the Roman empire. Revivals of Stoicism have occurred, most notably during the Italian renaissance (fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries) and, on a smaller scale, in the contemporary period as well. It originated very shortly after the time of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle in the thought of Zeno of Citium, a city on the eastern Mediterranean island of Cyprus. Zeno taught in Athens beginning around 300 BC, or shortly after the deaths of Plato and Aristotle, and broadly speaking his ideas can be understood as emerging from the Platonic-Aristotelian tradition while taking some of those ideas in a new direction. The central focus of Stoicism would always be ethics. Socrates had taken the view that the central question of philosophy is the good life for human beings, and this question would continue to hold a central position in the classical philosophies of Plato and Aristotle. The good life, all three believed, is the virtuous life. Happiness and virtue are one, in a deep sense that needed to be philosophically clarified and justified, and Stoicism from the beginning would appropriate this idea from Plato and Aristotle while developing it in some novel ways. As a general rule in Western intellectual history, a new movement such as Stoicism does not originate out of the blue but emerges organically from a prior movement or tradition, many of whose ideas are continued while others are modified or rejected, on the model of a conversation where the various interlocutors hold certain ideas in common while disagreeing about others. The Western tradition as a whole can be regarded as one long chain, to take a different metaphor, while every intellectual movement and thinker is a link in this chain. On the whole one finds far more continuity than discontinuity, although the disagreements and innovations have a way of catching our attention.

The starting point, we might say, for all of these thinkers—Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and now the Stoics—is that the highest good in human life is happiness (the Greek word is “eudaimonia,” which can be translated as happiness, well being, or flourishing), and that happiness is bound up in a fundamental way with virtuous conduct or a good character. A rational being—the kind of being that we are by nature—cannot be both happy and vicious. If many people believe that a person of bad character can be happy, even the happiest of all, this is false. The morally good life, the life that is proper to a rational being, and happiness are a kind of package deal, all these philosophers believed. They would disagree about the details and the implications of this basic idea, however. The idea would also survive into medieval Christian thought, albeit with much modification. We shall return to this later in the course.

The basic view of Zeno and later Stoic thinkers, both Greek and Roman—Chrysippus, Diogenes, Antipater, Panaetius, Seneca, Epictetus, and others—is that to achieve happiness, the highest good in human life, we must cultivate the virtues rather than devote our lives to the pleasures, power, prestige, or other worldly goods. Worldly goods come and go, but a virtuous character has a constancy about it and a permanence that rises above the contingencies of human life. A virtuous life is the natural condition of every human being, and while the constant pull of the world leads away from this, our happiness and highest good are one with a morally good character. The philosopher and all of us must direct our focus inward and away from the goods and happenings of the world. We might think it counterintuitive for a Roman emperor to hold such a view, a man who would spend so many of his years embroiled in Roman politics and at war with the empire’s enemies, but what we find in this series of reflections is a philosopher-king with one foot in the world of imperial politics and another in a private world of interior cultivation. By Marcus’ time, Stoicism had emerged as a popular philosophy among Roman intellectuals and cultural elites, and in this book we will find its author developing that philosophy further.

Stoicism gets its name from the painted colonnade or walkway (“stoa poikile”) that was located in the Athenian “agora” or public square and marketplace where Socrates had earlier conducted many of his conversations. It was in this beautiful covered walkway that Zeno and many of his fellow intellectuals would debate the ideas that would become the philosophy of Stoicism. The only complete Stoic texts that we possess belong to later Roman figures such as Marcus, Seneca, and Epictetus, while the Stoics in general, as can always be said of an important intellectual movement, disagreed about many of the details of this general philosophy while sharing an underlying worldview.

Marcus’ Meditations isn’t written in the fashion of a modern philosophical treatise but consists of numerous, loosely organized reflections on a series of themes relating to human life generally and to Marcus’ own life in particular. Remember that this isn’t a book intended for a public audience but for himself alone. The autobiographical material is included not merely as an exercise in self-indulgence but as a crucial part of this philosopher’s attempt to understand life in the most profound way possible. We will find a fair amount of repetition between chapters and an overriding mood of serenity and detachment from worldly affairs.

Let’s have a look at some of the more notable reflections from Book 1. He begins by acknowledging his personal indebtedness to family members and teachers, beginning in the very first sentence with two virtues that he owes to his grandfather. Where do the virtues come from? From parents, grandparents, teachers, and other positive role models in our lives as we grow up. To his father, he says, he owes “integrity and manliness” while to his mother “piety, generosity, … simplicity of living,” and a few other things (3). None of us is born with a good character but learns this in a proper social environment, if we are fortunate. He credits his tutor (the education of aristocrats was largely acquired at home at the hands of private tutors) with not becoming excessively attached to public entertainment and sports; the Greens and the Blues, by the way, which he mentions on page 3 were competing chariot racing teams whose fans were famous for getting more than a little carried away in their enthusiasm. His tutor also taught him “to tolerate pain and feel few needs; to work with my own hands and mind my own business; to be deaf to malicious gossip” (3).

From the first page, then, we find Marcus crediting his early role models for the lasting influence they had on his development. Virtues learned in childhood and youth often remain with us through life, and the qualities of character that this emperor now relied upon in his position and in his life had been acquired at this early stage, he says. Bad role models in youth, as Plato had also argued in the Republic, lead to bad behavior and mental turmoil through life, and it is a hypothesis with which Marcus would agree. He continues in this vein through the several pages of Book One, which like the rest of the book is written in the form of short paragraphs and aphorisms organized around a central topic. We begin to get a sense in these opening pages both of Marcus’ early role models and of a larger conception of ethics and the good life which he acquired under their influence and by which he still lives. Later it would be philosophers from whom Marcus would learn these same things on a higher or more abstract level. He credits the Stoic philosopher, teacher, and politician Rusticus, for instance, for teaching him, among other things, “to keep clear of speechifying, versifying, and pretentious language; not to walk around at home in ceremonial dress, or do anything else like that; to write letters in an unaffected style,” as he is now doing in the Meditations (4). His own writing style is unaffected and free of the jargon and stuffy formality that we often find in philosophical writing and public oratory. The art of public speaking or rhetoric was highly valued in the ancient Greek and Roman world and would often degenerate into empty formality, pretentiousness, and sophistry, and we find Marcus here studiously avoiding this habit. Again, it was a habit that was imparted to him from a teacher rather than something he was born with.

He mentions a number of other philosophers, poets, and rhetoricians from Apollonius to Sextus Empiricus, Fronto, Catulus, and others, acknowledging in every case what he learned from them especially by way of the virtues. The crucial part of all education, Marcus tells us, is not information alone but the example that the true teacher imparts, whether we’re speaking of professional teachers, family members, writers and intellectuals, or whomever they might be. From the Stoic philosopher Sextus Empiricus, for example, he says that he learned a great many things, including “the concept of life lived according to nature; an unaffected dignity; intuitive concern for his friends; tolerance both of ordinary people and of the emptily opinionated; … never to give the impression of anger or any other passion, but to combine complete freedom from passion with the greatest human affection; to praise without fanfare, and to wear great learning lightly” (4). By the end of this short chapter, we have an idea of Marcus’ conception of a virtuous character: it is the person whose life is centred around wisdom and truth, dignity and restraint, kindness and friendship, family and gentleness, courage and honesty, and a mild and pleasant disposition. The virtuous individual does not give offence to the gods or to reasonable human beings, while displaying strength of character and resoluteness in the face of difficulty. This individual combines in typically Roman fashion a virile and a humble quality, and the following chapters will spell out in more detail this basic picture of a well lived life.